What Are Immutable Data Structures?

Immutable data structures are collections that cannot be modified after creation. Instead of changing existing data in place, operations on immutable structures return new versions while preserving the original. This might sound inefficient at first glance—wouldn’t creating new copies for every change be wasteful? The key insight is that well-designed immutable structures use structural sharing to avoid unnecessary duplication.

When you “modify” an immutable data structure, only the parts that actually change are copied. The unchanged portions are shared between the old and new versions, dramatically reducing both memory usage and operation costs. This approach provides several benefits:

- Thread safety: Since data cannot be modified, multiple threads can safely access the same structure without synchronization

- Predictable behavior: Functions that receive immutable data know it won’t change unexpectedly

- Easier debugging: Data races and unexpected mutations are eliminated

- Efficient copying: Cloning becomes a lightweight operation

Building Blocks: The Cons Structure

The cons cell (short for “construct”) is one of the most fundamental immutable data structures, originating from Lisp. A cons cell is simply a pair containing two values: traditionally called the “car” (first element) and “cdr” (rest of the list).

[data|next] -> [data|next] -> [data|null]When you “add” an element to the front of a cons list, you create a new cons cell that points to the existing list. The original list remains unchanged and can still be referenced independently. This demonstrates structural sharing in its simplest form—the new list shares the tail with the original.

Original: [B|next] -> [C|next] -> [D|null]

New: [A|next] -> [B|next] -> [C|next] -> [D|null]

^

shared structureModern immutable data structures extend this concept to more complex forms like hash maps, vectors, and trees, using techniques like hash array mapped tries (HAMTs) and balanced trees to maintain efficiency.

A Real-World Story

Let me share a concrete example of how immutable data structures solved a critical performance problem in one of my systems.

I was working on a high-throughput pub-sub WebSocket system that needed to efficiently distribute data packets to thousands of clients based on their topic subscriptions. Each client could subscribe to multiple integer topics, and the system needed to handle a very high volume of incoming data packets that had to be routed to the appropriate subscribers.

The architecture separated the subscription management path from the distribution path to avoid contention, since distribution was the much hotter code path. Subscription state was maintained as a Map<u64, Vec<ClientId>>, mapping topic IDs to lists of subscribed clients.

Here’s how the original system worked:

- When a client sent a subscription/unsubscription request, the subscription task would:

- Update the map by adding/removing the client from the appropriate topic

- Make a deep clone of the entire map

- Send this cloned map to the distribution task via

tokio::sync::watch

- The distribution task used a biased

tokio::select!to monitor both:- The watch channel for subscription updates

- An MPSC queue for incoming data packets

- When the watch updated, the distribution task would update its local copy of the subscription map

- For every data packet, it would look up subscribers in this map and route accordingly

Why not use a sync::RwLock? Due to the extreme asymmetric access patterns (200 subscription updates/sec vs 100,000 distribution reads/sec), an RwLock would be unsuitable. Every write operation would acquire an exclusive lock blocking all readers, while frequent writes would constantly invalidate CPU cache lines on the hot read path. The memory barriers and synchronization overhead would add latency to every packet distribution operation, and the 500:1 read-to-write ratio meant frequent exclusive lock acquisitions would starve the critical read operations.

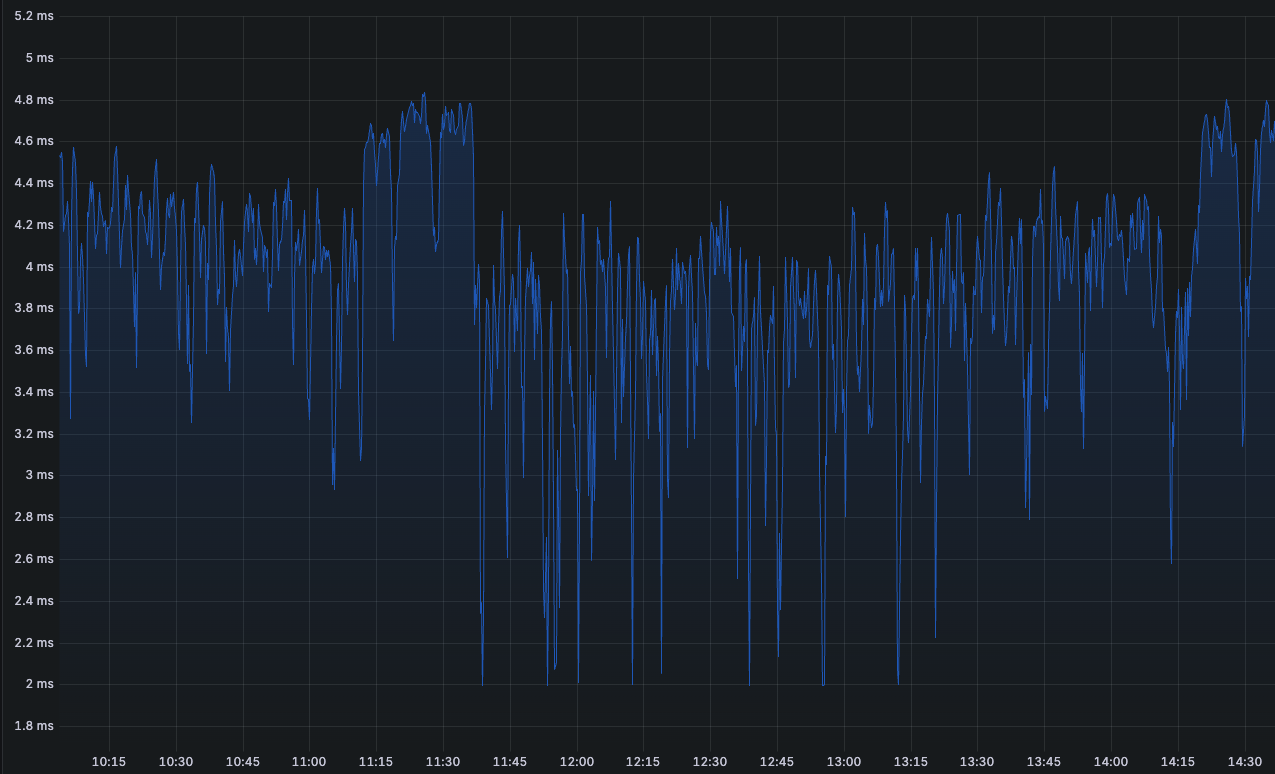

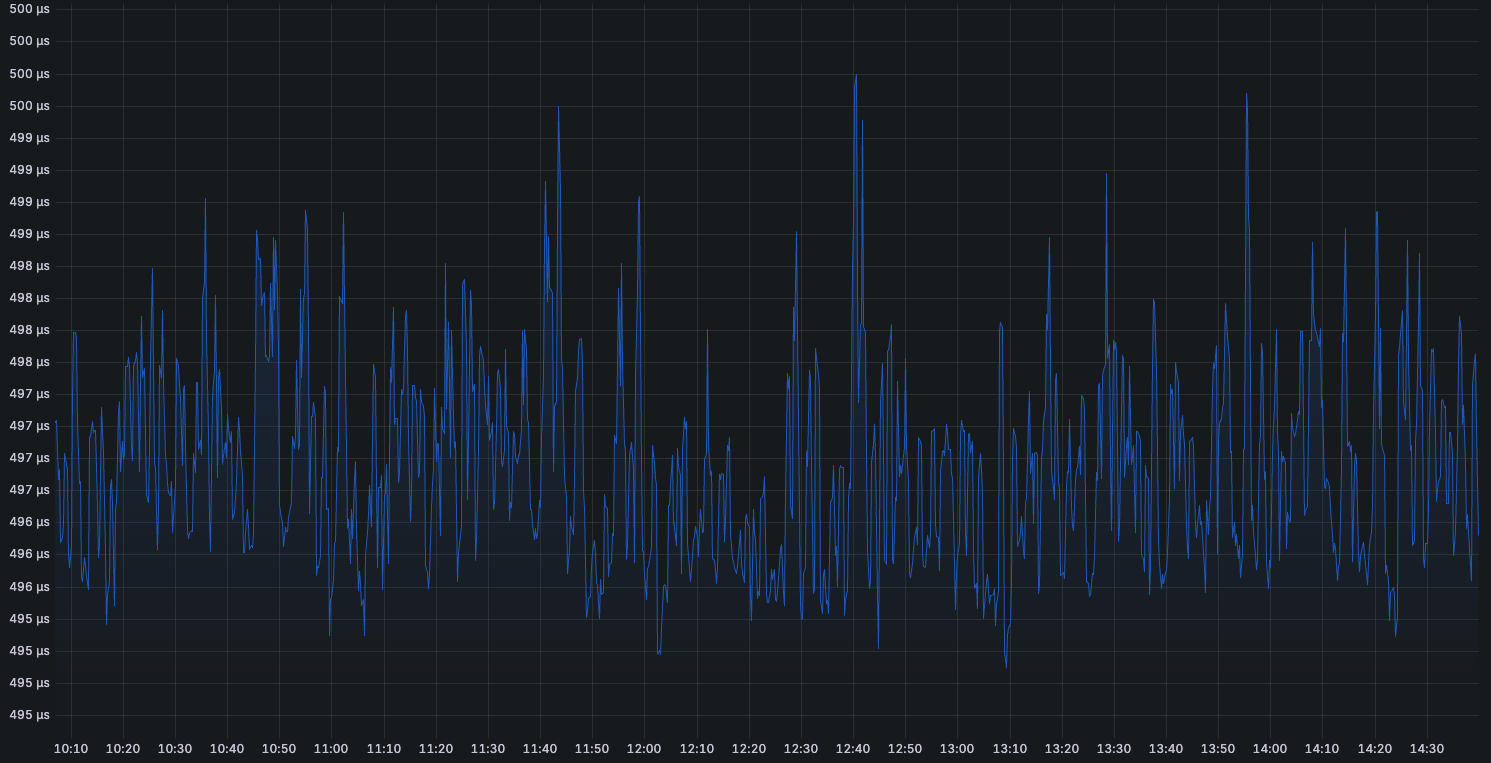

This design worked well initially, but as the number of clients and subscriptions grew, the latencies started going up. The deep clone operation on every subscription change was becoming prohibitively expensive—we were seeing p99.95 latencies of around 6 milliseconds just for the clone operation. With hundreds of subscription changes per second, this was creating significant overhead and potential blocking.

The Immutable Solution

I decided to experiment with immutable data structures using the imbl crate. The subscription map was changed from:

Map<u64, Vec<ClientId>>to:

imbl::HashMap<u64, imbl::Vector<ClientId>>Now, instead of deep cloning the entire map on every subscription change, the system would:

- Apply the subscription change, which would clone and modify only the affected parts while keeping unmodified parts shared through structural sharing

- Clone the map handle (essentially just cloning an

Arc-like reference) - Send this lightweight reference across to the distribution task

The results were dramatic: latency dropped from ~6ms to 500µs-1ms range—roughly an order of magnitude improvement!

See the before and after latency profiles.

This performance gain came from the structural sharing properties of the immutable data structures. When a client subscribed to a topic, only the specific topic’s subscriber list needed to be modified. All other topics in the map remained completely unchanged and were shared between the old and new versions. The “clone” operation became just copying a few pointers rather than deep-copying potentially thousands of subscriber lists.

Key Takeaways

Immutable data structures aren’t always the right choice—they come with important complexity trade-offs that need to be understood. Traditional mutable hash maps provide O(1) operations for lookups and updates, while immutable hash maps typically have O(log n) complexity due to their tree-based internal structure.

However, the story becomes more interesting when you factor in cloning costs. In scenarios where you need to copy data structures (like my pub-sub system), the effective complexity of mutable structures becomes O(1) for the update plus O(n) for a full clone—making the total operation O(n). In contrast, immutable structures handle both the update and the “clone” (which is really just creating a new reference to shared structure) in O(log n) time. Initially, the n was small, so the normal HashMap and full-clone worked just fine. But as it grew larger, the cloning cost started dominating the performance.

The key lesson here is that performance optimization is always nuanced and context-dependent. Just as a linear search through a small array might outperform a HashMap lookup due to hashing overhead (despite O(n) vs O(1) theoretical complexity), the “better” solution depends entirely on your specific use case, data sizes, and access patterns. Theoretical complexity tells only part of the story—always measure performance in your actual system before making decisions.